Tendulkar talks about his cars, his role as a father and the tough times in his career.

- 2000-2010 was a great decade: Tendulkar

- Retrospective: Sachin Tendulkar's Test career

- Tendulkar completes 23 years in international cricket

He was watching, absorbed, Shane Warne bowling in an Ashes series in England. It was the summer of 2005. I had that evening spent a good deal of time watching Tendulkar watch Warne. It was riveting.

Full of life

Full of lifeAnd now here he is, in a crisp, white shirt, black trousers, designer black shoes (of which more later), and an India blazer (the BCCI is hosting an awards ceremony downstairs, and he will have to be on stage to accept the first award of the night for his hundred international centuries).

He has also emerged – unscathed – from a minor sartorial misadventure: two buttons on his jacket broke, and have just been stitched back on.

There is something about people who have been made larger than life on TV – or, in Tendulkar’s case, a larger than life personality made larger still - there is something different about these people, when you meet them in person, not in work clothes.

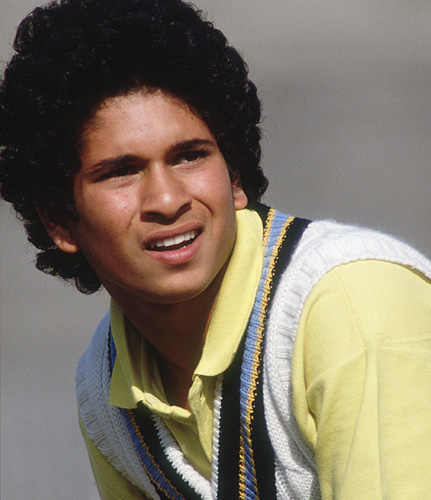

He looks compact, the long hair that he had for a change having given way to the familiar close-cropped curls.

His handshake is firm but fleeting. We are sitting facing each other on two chairs that have been pulled aside from the tables being set for dinner.

He sits hunched forward, hands clasped in front of him. He speaks very softly, so that I have to lean even further forward to hear what he is saying.

His face is mobile, and expressive. There emanates from him, even in this relaxed setting, a sort of charge, a kind of hyperactive intensity.

Tendulkar was the first sporting hero I had who was younger than me. I first saw him play when he was 16, and I was 20.

For the first time in my life, I was in awe of someone I was older than. When I tell him how life-altering something such as this can be at the age of 20, he smiles (lips twitching and turning up, face getting all creased up); he seems genuinely pleased, almost bashful.

“It is very kind of you to say that.” And I think of the inner child in him, the one that still wants to bat and bat.

Friendly figure

Wary that I am straying into cricket talk, I ask him instead which of his cars he enjoys driving the most.

“The BMW5. It is sporty and comfortable. It is a magnificent car. I go for a spin in it very early in the morning – 3am, 4am.”

His son, Arjun, is around, and I wonder if Sachin thinks Arjun is a better player than Sachin was at his age.

“I don’t like comparisons. Every individual has his own identity. What he wants to be is his choice. People should judge him on merit.”

It must be hard, travelling all the time, being away from one’s children. “Yes, it is very tough. That is why my wife – who is a gold medallist in medicine – gave up her career. It would have been impossible if both of us had been away.”

What sort of a father is he? What sort of a father would he ideally like to be? “I would like to be a friend who is always there to guide them. I would like to be the person to whom they can come and talk to about anything they want.”

Then there is a pause. Without any prompting, Tendulkar says: “I would like to emulate my father in this respect. I miss him very much. All this I have now, and he is not there to see any of it. Not having him is the only void in my life.”

His face crumples a bit, and I think of that century against Kenya in the 1999 World Cup, the one he scored after returning from his father’s cremation, as moving and authentic a filial tribute as one has ever seen.

It seems appropriate to talk about happier things. So I ask him what he enjoys spending money on.

“I love food, shoes, cars, perfumes.” The perfume he is wearing at the moment is Comme des Garcons (thanks to Wikipedia, I know that it is a Japanese label that introduced in 1998 the “anti-perfume Odeur53, a blend of 53 non-traditional notes to create a modern and striking scent”).

The shoes are Berluti (again, Wiki tells me that it is a French “company that manufactures and retails a very exclusive luxury brand of shoes and boots solely for men”).

Down to earth

As he talks, images of him lighting up cricket grounds all over the world swirl and roil inside my head: Bloemfontein; Sharjah; Perth; Chennai; Old Trafford, Sydney… And I chance my luck, and get started on the cricket. Not a lot of it, just a bit.

“No, let’s talk about cricket. I love talking about cricket. It is all I have ever done – talk about cricket and play cricket – all my life.”

Seeing him, his body language, his tone, his courteousness, I am reminded again of why the Tendulkar phenomenon is actually what it is.

He is a world-beater, a global citizen; he is smart, well dressed, he drives sexy cars; a self-made man, he is staggeringly wealthy; he is Indian cricket’s first global brand.

At the same time, he appears to exemplify certain cherished Indian values: humility, deference to elders, and respect for all things that ought to command respect. With Tendulkar, we can have it both ways, and we are delighted about that.

Tendulkar has achieved in the game what no one ever has, or is ever likely to. But contentment is an elusive thing, especially in the case of someone as ambitious and gifted as he is. Has he found it?

“I am happy. I pray to god that I can always value and respect whatever has come my way. My family’s influence in all this is crucial. At no stage has my family got carried away with anything. Whenever anything good happens in life, we offer sweets to god.”

Tough times

But in an international career spanning 23 years, the going can never be all good. “No, not at all. The darkest period in my life was when I was undergoing treatment for my tennis elbow in 2004 and the surgeries to do with it. It was unbelievably painful. It is the most that I have ever endured. I asked my wife to record some of that on a camera. I could not sleep at night. I thought that my career was over.”

It wasn’t over, of course. It still isn’t. And while the injury may have been the most painful thing Tendulkar has ever endured, there is something else that terrifies him. “I am scared of natural calamities. Earthquakes, tsunamis, you know, that sort of thing.”

He looks at his fancy watch. He does not fidget. But I know that my time is up. So I make to wind up. “I have to go downstairs,” he says. “I am sorry.” And with a nod and a wink, he melts away.

Martin Amis writes in one of his essays that when a writer goes to interview a person he admires, he is constantly hoping for one of three things to happen: a full-scale nervous breakdown of the interviewee in the middle of the conversation; or some scandalous, never-heard-before sort of revelation; or the tentative beginning of a friendship.

Given that the interviewee in this instance was one of the world's most private men, I knew that the likelihood of anything remotely resembling those things was less than zero.

Only this happens. When I wake up the following morning, I see that I have missed a phone call from an unlisted number. A couple of hours later, I get another call - again, an unlisted number.

“Hi, Soumya,” the familiar voice at the other end of the line says. “This is Sachin.”

Wary that I am straying into cricket talk, I ask him instead which of his cars he enjoys driving the most.

“The BMW5. It is sporty and comfortable. It is a magnificent car. I go for a spin in it very early in the morning – 3am, 4am.”

His son, Arjun, is around, and I wonder if Sachin thinks Arjun is a better player than Sachin was at his age.

“I don’t like comparisons. Every individual has his own identity. What he wants to be is his choice. People should judge him on merit.”

It must be hard, travelling all the time, being away from one’s children. “Yes, it is very tough. That is why my wife – who is a gold medallist in medicine – gave up her career. It would have been impossible if both of us had been away.”

What sort of a father is he? What sort of a father would he ideally like to be? “I would like to be a friend who is always there to guide them. I would like to be the person to whom they can come and talk to about anything they want.”

Then there is a pause. Without any prompting, Tendulkar says: “I would like to emulate my father in this respect. I miss him very much. All this I have now, and he is not there to see any of it. Not having him is the only void in my life.”

His face crumples a bit, and I think of that century against Kenya in the 1999 World Cup, the one he scored after returning from his father’s cremation, as moving and authentic a filial tribute as one has ever seen.

It seems appropriate to talk about happier things. So I ask him what he enjoys spending money on.

“I love food, shoes, cars, perfumes.” The perfume he is wearing at the moment is Comme des Garcons (thanks to Wikipedia, I know that it is a Japanese label that introduced in 1998 the “anti-perfume Odeur53, a blend of 53 non-traditional notes to create a modern and striking scent”).

The shoes are Berluti (again, Wiki tells me that it is a French “company that manufactures and retails a very exclusive luxury brand of shoes and boots solely for men”).

Down to earth

As he talks, images of him lighting up cricket grounds all over the world swirl and roil inside my head: Bloemfontein; Sharjah; Perth; Chennai; Old Trafford, Sydney… And I chance my luck, and get started on the cricket. Not a lot of it, just a bit.

“No, let’s talk about cricket. I love talking about cricket. It is all I have ever done – talk about cricket and play cricket – all my life.”

Seeing him, his body language, his tone, his courteousness, I am reminded again of why the Tendulkar phenomenon is actually what it is.

He is a world-beater, a global citizen; he is smart, well dressed, he drives sexy cars; a self-made man, he is staggeringly wealthy; he is Indian cricket’s first global brand.

At the same time, he appears to exemplify certain cherished Indian values: humility, deference to elders, and respect for all things that ought to command respect. With Tendulkar, we can have it both ways, and we are delighted about that.

Tendulkar has achieved in the game what no one ever has, or is ever likely to. But contentment is an elusive thing, especially in the case of someone as ambitious and gifted as he is. Has he found it?

“I am happy. I pray to god that I can always value and respect whatever has come my way. My family’s influence in all this is crucial. At no stage has my family got carried away with anything. Whenever anything good happens in life, we offer sweets to god.”

Tough times

But in an international career spanning 23 years, the going can never be all good. “No, not at all. The darkest period in my life was when I was undergoing treatment for my tennis elbow in 2004 and the surgeries to do with it. It was unbelievably painful. It is the most that I have ever endured. I asked my wife to record some of that on a camera. I could not sleep at night. I thought that my career was over.”

It wasn’t over, of course. It still isn’t. And while the injury may have been the most painful thing Tendulkar has ever endured, there is something else that terrifies him. “I am scared of natural calamities. Earthquakes, tsunamis, you know, that sort of thing.”

He looks at his fancy watch. He does not fidget. But I know that my time is up. So I make to wind up. “I have to go downstairs,” he says. “I am sorry.” And with a nod and a wink, he melts away.

Martin Amis writes in one of his essays that when a writer goes to interview a person he admires, he is constantly hoping for one of three things to happen: a full-scale nervous breakdown of the interviewee in the middle of the conversation; or some scandalous, never-heard-before sort of revelation; or the tentative beginning of a friendship.

Given that the interviewee in this instance was one of the world's most private men, I knew that the likelihood of anything remotely resembling those things was less than zero.

Only this happens. When I wake up the following morning, I see that I have missed a phone call from an unlisted number. A couple of hours later, I get another call - again, an unlisted number.

“Hi, Soumya,” the familiar voice at the other end of the line says. “This is Sachin.”